Exploitation of Africa’s Coffee Family Farmers from Fair Earnings While the Rest of the Coffee Supply Chain Players Enjoy Healthy Margins

Introduction.

Coffee is one of the world’s top traded commodities, ranked highly among products like crude oil, gold, and natural gas. Indeed the coffee industry is one of the most important agricultural sectors worldwide. Evidence shows that such top commodities have truly delivered life-changing monetary value for the populations involved in their primary production in the countries of origin. For example, oil has contributed immensely to the wealth of its producing citizens. But the same cannot be said for millions of African farmers who break their backs to produce extremely high-quality coffee. The world is enjoying the farmers’ fine coffee, the stock exchanges in Europe and America are swimming in fat coffee profits, but the poor farmers back in Africa are left to clutch onto ‘peanut’ incomes that cannot sustain even one decent meal per day. This is blatant exploitation of African farmers and no justification can suffice.

The majority of Africa’s population works in the agriculture sector (59.4% of total employed persons in sub-Saharan Africa worked in the agricultural sector in 2019) and coffee being a primary agricultural product, then the poor prices paid to African farmers is a major cause of extreme poverty in the region. The share of Agriculture in GDP is still higher in Africa compared to developed nations (Agriculture share per GDP was 15.3% in sub-Saharan Africa in 2018)2. It, therefore, follows that a key contributor to Africa’s GDP has been dealt a devastating blow not by genuine market forces but by carefully designed exploitation targeted at condemning the African farmer to ‘terminal’ poverty.

Coffee is a popular commodity in the global market, and its price is an essential indicator for traders, but it is more crucial for farmers in developing countries, especially in Africa. Farmers from Africa are exploited due to poor prices which are currently not enough to cover production costs. Prices paid to coffee farmers globally are lowest in Africa.

[1] Statista, 2019 Year

[2] The World Bank

1. Historical Coffee Prices

- Coffee trading prices are decreasing since 2011. This decline is predicted to continue after 2020;

- Market price of Arabica is higher than Robusta but more unstable;

- Prices paid to farmers are lower in Africa than other regions;

- Coffee producer prices are decreasing which is reducing the earnings of farmers.

1.1. Coffee prices paid to African farmers compared to farmers from other regions.

For coffee farmers, the key indicator is “Prices paid to Farmers” i.e. producer prices which shows us real revenues for the farmers in the agricultural sector. We used data from the International Coffee Organization, which provides price trends for several coffee exporting economies. Figure 1 analyzes Arabica prices for major exporting countries compared to several African economies between 2000-2018. Farmers in Colombia, India and Brazil are getting higher prices on their crops compared to African countries – Ethiopia, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon.

Figure 1 : Prices Paid to Farmers

The price of “Brazil Naturals” coffee (a species of Arabica) for farmers advanced by 37.6% between 2000–2018 in Brazil, when the rate for the same coffee in Ethiopia was only 25.3%. Differences between producer prices mostly stayed the same during the last 20 years, i.e. Arabica coffee is still cheaper in Africa.

Robusta beans are the main coffee export segment for several African countries. Historical prices paid to farmers in Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Uganda and Central African Republic) are mostly lower compared to prices in Brazil and India (Figure 2). It can be said that producers of Robusta beans in African countries are also struggling with unfair prices, but the difference is lower compared to Arabica sector. African coffee exporting economies saw high growth rates in the price of Robusta beans as their prices were too low in the early 2000s .

Figure 2 : Prices Paid to Growers

Figure 3 shows regional price averages for each coffee group (2018 year). Regional averages are calculated by countries’ weights in total production (11 countries for Arabicas group and 7 countries from Robustas group). Calculations cover coffee exporting economies which are recording the major part (2/3) of global coffee production.

The average price in Africa for Arabica coffee is 70.4 US cents per pound when price is 37.6% higher in Latin America and 41.5% higher in India.

The price of Robusta is less than Arabica – 58.4 US cents per pound in Africa. Prices in Latin America and India are higher, respectively; 78,5 US cents and 67.4 US cents

Figure 3 : Average Prices Paid to Growers By Region

1.2. Coffee trading historical prices.

We are using coffee prices from the International Coffee Organization (ICO) to analyze global general coffee price trends. International Coffee Organization provides the coffee ICO composite index, which includes all major coffee groups with its weights in total production. The ICO index is introducing raw coffee trading prices in the international market.

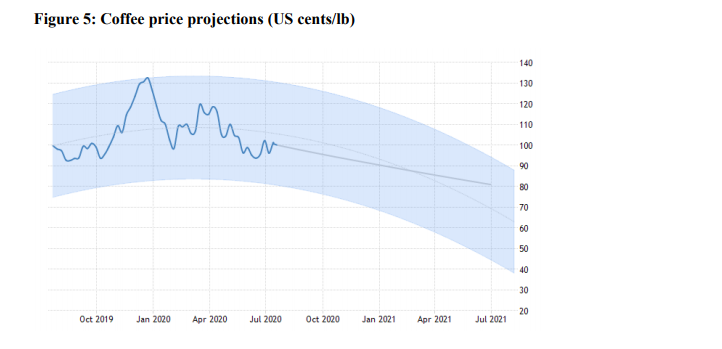

The ICO index (USD cent/lb) was sharply increasing between 2002–2011 (Figure 4), achieving 210.4 US cents per pound in 2011, which was the historical highest point. Average coffee prices are plunging after 2011, recording 109.0 in 2018 (the lowest point between the last 11 years). The coffee price decline exacerbates farmers’ problems and makes the future of the industry more uncertain. The coffee will be traded below 100.0 after 2020 (Trading Economics projections, Figure 5) according to the recent forecast. The revenues of coffee farmers are negatively affected by the global market price decline, especially when incomes of farmers have a small share in the coffee chain value, i.e., coffee farmers are the most vulnerable group in the coffee chain.

Figure 4 : ICO Composite Indicator

ICO index consists of four major different coffee groups:

- Colombian Milds

- Other Milds

- Brazilian Naturals

- Robustas

Figure 6 represents price trends for each coffee category. We can assume that general coffee price fluctuations over the last ten years were mostly driven by Arabica species (selected Colombian Milds, Other Milds and Brazilian Naturals). All of these groups showed their highest peak in 2011 and then are decreasing until today. Compared to other groups, Robusta is cheaper, and more stable fluctuations characterize its price. Both groups of Milds are more expensive – Colombian Milds and Other Milds, respectively, 136.7 and 132.7 US cents/lb.

Figure 6 : ICO Index by Group

1.3 Roasted coffee historical retail prices in importing countries.

Retail prices of roasted coffee are significantly higher as roasters are the key actors in the coffee chain. Roasting coffee is a different industry altogether, but trends in that market are still interesting for this report. Prices in major importing coffee consumer countries are mostly ranging between $3 and $8 in 2018 (see Figure 7).

Retail prices of roasted coffee are significantly higher as roasters are the key actors in the coffee chain. Roasting coffee is a different industry altogether, but trends in that market are still interesting for this report. Prices in major importing coffee consumer countries are mostly ranging between $3 and $8 in 2018 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7 : Retail prices of roasted coffee in selected importing countries

Figure 7 analyzes five different coffee importing countries from different regions (France, Germany, USA, Japan and the Russian Federation). Average prices decreased between 2011–2019, but the decline was not too significant, as in previous examples. Research also analyzes roasted coffee prices for 28 importing economies, including 23 countries from Europe (according to ICO data). The median price between our selected 28 major importing countries was 5.63 USD per lb.

Compared to raw coffee prices, the roasted coffee market shows less fluctuation; therefore, prices remain more stable. This illustrates the fact that the most problematic issue in the coffee industry are low prices to growers.

2. Coffee Production Costs vs Earnings of Farmers in Africa

- Coffee farming is labor intensive;

- African households frequently use family labor in coffee production that makes real production costs hard to determine;

- African farmers’ share in the roasted coffee value chain is estimated to be between 8%–13% compared to 15.7% in India and 14.9% in Brazil;

- The Fairtrade minimum price for Arabica coffee is 140 US cents per pound. Real prices in Africa are significantly lower (74 US cents per pound).

Coffee production costs are a vital indicator for farmers’ profitability. If prices are below the cost of production, farmers are losing money. The growing global supply of coffee is decreasing coffee prices, but production costs have stayed high in many countries.

Coffee farming is a labor-intensive activity accounting for 70% of total cost production (ICO 2015). Costs of production are difficult to assess as small-scale farmers rely on family labor and occasionally hired workers. Due to changing rural demographics, smallholder farmers must hire labor to support their farming activities that were traditionally handled by the family. According to ICO (2015), costs of production are generally lower for smallholding farms than estate farms. In Burundi, for example, the average cost of production for a farmer who adopts good agricultural practices (fertilizers and labor) varies between 50.1 US cents to 57.6 US cents per tree. The average size of a farm is 100 trees[1].

Fairtrade coffee price is a minimum price which covers the costs of production by making sure it respects fundamental human rights and provides sustainable living conditions for farmers’ families and communities[2].

Fairtrade minimum price for 2018 was 140 US cents per pound for Arabica coffee. Farmers need an extra 20 cents per pound (Fairtrade premium) to be able to invest.

Growers’ price is not playing a dominant role in consumer coffee price-making when roasters and other shareholders are getting higher earnings. Figure 8 displays six African countries with their shares in the roasted coffee value chain. Roasted coffee price is taken as a median price from major 28 importing countries. Prices to farmers are weighted according to total coffee production breakdown by categories for each country. Farmers’ shares in the roasted coffee value chain are ranging from 8.7% to 12.6% in the selected example. Farmers’ share in the value chain is highest in Angola – 18.0%, when the share is even less in major African coffee exporters, Ethiopia and Uganda, respectively 12.6% and 10.0%. Same ratios are higher outside of Africa, 15.7% in India and 14.9% in Brazil.

[1] International Coffee Organization. (2015). Sustainability of the coffee sector in Africa. International Coffee Council 115th Session.

[2] Fairtrade is a global movement with a strong and active presence in the UK, represented by the Fairtrade Foundation.

The roasted coffee value chain consists of a number of shareholders, including local intermediaries, international traders: exporters, insurance, and freight fees of importing/exporting, roasters, retailers, taxes.

Figure 8 : Retail prices of roasted coffee in selected importing countries

If we analyze coffee production and consumption numbers in all countries, the farmers’ contribution rate could be slightly growing. According to several publications, producer share in the coffee value chain is ranging from 10% to 20% (when the roasters add approx. 30% of total value). Intermediaries, traders and retailers are also taking important portions from total revenue. Share of farmer value was 20% during the end of the previous century, but now it is decreasing. Calculations in the research showed that the rate is nearly 10% in African exporter countries. A similar indicator was higher in some non-African exporter countries as the prices paid to growers are higher.

3. Lost Amounts by African Coffee Farmers.

- Due to unfair trade terms, lost amounts for Ethiopian farmers are 713.1 million USD and 229.7 million USD for farmers in Uganda;

- It is estimated that African coffee farmers are losing $1.47 billion every year from exploitative pricing of their crops. African families are vulnerable to unfair prices.

In the coffee industry, farmers’ value is mostly ranging between 10-20%, which is unfair. In African countries, the rate is lower (Figure 8). According to the Fairtrade Foundation, the minimum fair price for Arabica coffee should be 1.4 USD per pound when African farmers are receiving only 0.74 USD (average). If African farmers were paid higher amounts, they would be able to cover all costs and to increase their productivity.

Figure 9 represents lost amounts for farmers in African coffee exporter countries. The research develops a hypothesis of fair prices and used specific conditions to measure lost amounts:

- Prices paid to growers will be increased from current levels to fair trade minimum.

- The estimated fair price for Robusta is calculated according to the Fairtrade price for Arabica and price differences between Arabica and Robusta.

- All countries’ production could be sold at new prices. The coffee supply will stay as a fixed variable.

Figure 9 : Amounts Lost by African Farmers Every Year

Ethiopia will mostly advantage from fair trade prices in the selected example, where lost revenue is 713.1 million USD per year, which should go to farmers directly. Coffee farmers in Uganda benefit by 229.7 million USD from fair trade terms. Côte d’Ivoire will gain 71.2 million USD.

Farmers in minor coffee industry countries are also losing substantial revenue from unfair trade terms: DRC – 22.7 million USD, Cameroon – 22.4 million USD and Togo – 1.4 million USD.

We tried to calculate estimates for the whole African continent. Countries, in our example (Figure 9), are producing 72.4% of African coffee. Weighted average share in the coffee value chain is only 11.2% for selected economies. If lost amounts rates are similar to other African countries, the total lost amounts for Africa could be 1.47 billion USD per year.

Conclusion

Farmers in Africa are struggling with low producer prices in the coffee sector. Their share in the coffee value chain is insignificant. Decreasing prices and high production costs make the African coffee sector unprofitable. Farmers have no power to influence market prices and are forced to accept unfair prices. Low revenues cannot increase productivity in the industry and smallholders remain in poverty.

Lost amounts for African coffee farmers from unfair producer prices are estimated to be 1.47 billion USD yearly. These amounts are crucial for African producers from several countries where coffee is their major exporting product.

It is now clear that what is happening to African coffee farmers is akin to bleeding the leech to fatten the heifer. Let no one peddle any sense of false hope in this exploitative and abhorrent hostage situation for the poor coffee farmer. For the second most traded commodity in the world, this situation is untenable moreso for the African farmer, who produces some fine quality coffee, but receives the lowest prices of all growers, globally. These coffee farmers are existentially threatened.

There is no solution to the woes of Africa’s coffee farmers outside a political one. This exploitation can be ashamed by changing the coffee trading rules within the World Trade Organization (WTO).

References

Fairtrade Foundation. www.fairtrade.org.uk/

Fairtrade International. (2019). Monitoring the scope and benefits of fair trade.

International Coffee Organization. (2015). Sustainability of the coffee sector in Africa. International Coffee Council 115th Session.

International Coffee Organization. Statistical database.

Slob, B. (2006). A fair share for smallholders: A value chain analysis of the coffee sector. SOMO.

Statista. Statistical database – Coffee worldwide.

Talbot, J. M. (1997). Where does your coffee dollar go?: The division of income and surplus along the coffee commodity chain. Studies in comparative international development, 32(1), 56-91

The World Bank. Open Data.

Tuvhag, E. (2008). A Value Chain Analysis of Fairtrade Coffee-With Special Focus on Income and Vertical Integration. Department of Economics, Lund University.